Oct 2000, Vol. 5 No. 1

Exploding like a firecracker from the ocean’s surface, the wide-shouldered mako made a triple acrobatic leap before stripping 250 yards of fly line, sounding rapidly into the depths of the Pacific. Fighting a mako for forty minutes is not an unusual outcome—more like the rule.

Exploding like a firecracker from the ocean’s surface, the wide-shouldered mako made a triple acrobatic leap before stripping 250 yards of fly line, sounding rapidly into the depths of the Pacific. Fighting a mako for forty minutes is not an unusual outcome—more like the rule.

It is hard to match the thrill of visually casting to a mako shark. Besides the aerobatics associated with casting to other large saltwater species such as sailfish, marlin, and tarpon, the angler must contend with the mako’s brute strength, all the while admiring the beauty of its sleek, compact body.

Fly-fishing for mako shark is at once terrifyingly active and deeply philosophical, one of the most challenging (and some say frustrating) examples of conservation fly-fishing. Even when hooked, the shark always wins: the sandpaper coarseness of its skin and tail either breaks the fly line (usually during a jumping episode), or the fish is reeled in and released at the side of the boat. Once a mako is hooked, the boat follows the direction of the shark—otherwise the shark would strip the reel. If the angler is successful in bringing the mako to the boat, a custom-made gaff clipped to the line gently pulls the barbless mackerel-patterned fly from the shark’s mouth.

A cousin to the Great White and salmon sharks, the short-fin mako, colored from olive to cobalt, is considered a top-of-the-pyramid ocean predator. The species, members of which have been clocked at speeds up to 40 miles per hour, covers a wider range that the great white. And unlike their more famous cousins, mako hunt and feed primarily on live prey.

A cousin to the Great White and salmon sharks, the short-fin mako, colored from olive to cobalt, is considered a top-of-the-pyramid ocean predator. The species, members of which have been clocked at speeds up to 40 miles per hour, covers a wider range that the great white. And unlike their more famous cousins, mako hunt and feed primarily on live prey.

I was aboard guide Conway Bowman’s boat, in the middle of the “Mako Triangle”—an area known to most as the “California Bight,” the Pacific Ocean between San Clemente, California and Tijuana, Mexico. Here, deep-water canyons have become prime habitat for mako spawning: after a gestation period of two to three years, the mako give live birth to as many as 15 pups. If the pups survive without being eaten by their mother or other mako, they are ready to prey. Schools of sardine, herring, and mackerel feed the sharks until they weigh between 400 and 500 pounds. At maturity, the sharks leave for destinations unknown—amazingly, nearly nothing is known about their maturity or adult whereabouts.

The 50-minute boat trip off San Diego, aboard Bowman’s 18-foot Parker outboard, is a bone-jarring roller coaster of a ride, not for the faint of heart. Despite the jarring trip, on my first mako excursion, Bowman and I arrived at the fishing grounds in good spirits; Bowman proclaimed “This looks like a great mako day.” The dark gray Pacific Ocean was shrouded by fog, and three-foot southerly swells collided with a cross chop. I swallowed hard and nodded in a way that I hoped seemed enthusiastic.

The 50-minute boat trip off San Diego, aboard Bowman’s 18-foot Parker outboard, is a bone-jarring roller coaster of a ride, not for the faint of heart. Despite the jarring trip, on my first mako excursion, Bowman and I arrived at the fishing grounds in good spirits; Bowman proclaimed “This looks like a great mako day.” The dark gray Pacific Ocean was shrouded by fog, and three-foot southerly swells collided with a cross chop. I swallowed hard and nodded in a way that I hoped seemed enthusiastic.

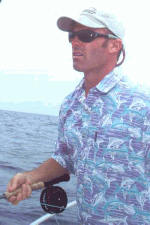

A third-generation San Diegoan, the 34-year-old Bowman is a beachboy at heart. When he isn’t fishing or working at his other day job, managing the Murray Reservoir in nearby La Mesa, he takes the surfboard off his car and heads for the waves. But fishing is his passion; he grew up fishing for bluegills, then graduated to calico bass. Always fascinated by mako, Bowman developed his technique over time, experimenting with a variety of flies and bait. Now he’s a huge mako fan, with serious interest in conservation of the species and a lot to say on those anglers who catch and kill the fish for food.

Bowman is a true angler, doing it for the joy of fishing. That doesn’t mean he’s not serious, though: he’s recorded the exact location of each mako release achieved from his boat. Bowman begins each trip with some information gathering. On our trip, he used his GPS (global positioning system) device to check the depth (less than 100 fathoms), water temperature (70 degrees), and current drift (southerly). This information is not just statistical—Bowman knows exactly where he wants to fish and, more important, the direction he wants the boat to drift.

Slowing the boat, Bowman next lowered a chum bucket filled with mashed bonito tuna. Particles of fish began to drift out of the bucket, clouding the water with fish particles and oil. “Power chumming,” we motored until the chum line stretched about half a mile. The location of the line was highlighted by a flock of terns and a few shearwater and hermann gulls, all looking for a feast along the chum line. While we waited for the mako to arrive, Bowman talked about his love for the shark, their strength and beauty, all the while tying steel leaders using his homemade flies.

Slowing the boat, Bowman next lowered a chum bucket filled with mashed bonito tuna. Particles of fish began to drift out of the bucket, clouding the water with fish particles and oil. “Power chumming,” we motored until the chum line stretched about half a mile. The location of the line was highlighted by a flock of terns and a few shearwater and hermann gulls, all looking for a feast along the chum line. While we waited for the mako to arrive, Bowman talked about his love for the shark, their strength and beauty, all the while tying steel leaders using his homemade flies.

The first mako approached the boat in less than an hour. Fishing for mako is visual fly-fishing; while the angler uses the same baiting and casting routine for each shark, no two sharks ever react the same. Bowman began with a spinning rod, baiting it with a mackerel head to entice the shark closer. Once the mako took notice and began to follow, he tossed chunks of mackerel, trying to lure the mako within casting distance. (If a shark is about three feet long, Bowman recommends the 12-weight rod; larger sharks require a heavier 16-weight rod.)

The mako came closer, eating the mackerel chunk. Bowman warned me to keep the fly off the water during this process: He doesn’t want the mako tempted too soon or too close to the boat. If the shark leapt into the boat, explained Bowman, “it would be disastrous. The mako would tear this boat apart.”

The mako came closer, eating the mackerel chunk. Bowman warned me to keep the fly off the water during this process: He doesn’t want the mako tempted too soon or too close to the boat. If the shark leapt into the boat, explained Bowman, “it would be disastrous. The mako would tear this boat apart.”

The mako receded a bit and, at Bowman’s signal I tossed the fly—but to no avail. Usually, if an angler is successful here, the battle begins. However, mako don’t usually give an angler a second chance; but this one was different. Contrary to the rule, the mako returned, majestic as ever. This time, after another taste of mackerel, it grabbed the fly—and I hooked it with all my might.

I’m an experienced fly fisherman, and an accomplished diver. In fact, I had dived with mako sharks, which, while intimidating, soon came to seem serenely beautiful in that quiet underwater world. But neither experience helped me here—maybe they even served up a false sense of security.

I’m an experienced fly fisherman, and an accomplished diver. In fact, I had dived with mako sharks, which, while intimidating, soon came to seem serenely beautiful in that quiet underwater world. But neither experience helped me here—maybe they even served up a false sense of security.

All security went out the window the moment I hooked the shark. It reared up, heading full-steam toward the boat, which offered the negligible protection of suddenly skimpy two-foot gunwales. I was all reaction and adrenaline, wrestling for control for maybe ten seconds—and then the shark stripped the line, which spun from my reel with a high whine. It took me a few minutes to recover, and quite a bit longer to digest the fact that my opponent was a shark half my size, a three-footer.

During two half-day trips, photographer Don Brandos, Bowman, and I had the opportunity to catch and release six mako, each of which reacted differently to our presence. Some did aerobatics; others circled the boat as if we were the prey, and a couple “bulldogged” (a term used by tuna fisherman for sounding or heading down). That’s one of the reasons Bowman loves to fish for mako. Not only is it a visual sport that doesn’t require trolling, each fish has its own personality, and all are aggressive and unpredictable.

When the next mako, a six-footer, came lurking, I gratefully yielded to Bowman, giving him an opportunity to prove his angling prowess. After that. I released several other three-footers, each time feeling more confident, and each time reveling in the rush of the release.

When the next mako, a six-footer, came lurking, I gratefully yielded to Bowman, giving him an opportunity to prove his angling prowess. After that. I released several other three-footers, each time feeling more confident, and each time reveling in the rush of the release.

Four hours later, the chum bucket was empty, and our day of mako fishing was over. I endured another rough ride back to the marina, this time with every muscle aching from the fight. Bowman was quiet, but I did catch something about “California dreaming”—a dream in which the thrill and majesty almost overwhelm, and in which the shark always wins.

If you go:

Conway Bowman: Call 619-286-4625, e-mail info@bowmanbluewater.com, or go to www.bowmanbluewater.com. Mako fly fishing season runs from May to November. Bowman prefers to fish five days before the phase of either the new or the full moon (when tidal movements attract bait, which attracts the sharks). A half-day fishing trip costs $250.00.