May 2000, Vol. 4 No. 8

The shimmering gold of the man’s silk shirt made him seem to sparkle amidst the crowd of prostrating pilgrims. Reaching his hands towards heaven, he bent his knees to the stone courtyard, then flattened his body as he slid forward into a prone position, using envelope-sized mats to protect the palms of his hands.

The shimmering gold of the man’s silk shirt made him seem to sparkle amidst the crowd of prostrating pilgrims. Reaching his hands towards heaven, he bent his knees to the stone courtyard, then flattened his body as he slid forward into a prone position, using envelope-sized mats to protect the palms of his hands.

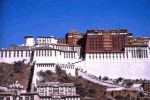

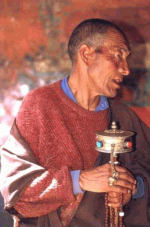

For Tibetan Buddhists, the Potala, the winter palace of the exiled Dalai Lama, is a popular destination for pilgrimage. Along the road leading to Lhasa, it is common to see groups of monks and laypeople, all flattening their bodies to the ground, asking the Buddha for benevolence. The practice is most frequent on the auspicious holy days of the eighth, fifteenth, and thirtieth of each month. Elderly Tibetans are especially well-represented, and some visit the palace daily, circumambulating its perimeter in prayer. The building itself is opened to the public on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

Stunningly dominating the skyline of Lhasa atop the crest of Marpo Ri hill, the seventh-century Potala is considered Lhasa’s most holy destination for a pilgrimage. Winding up the hill, a stone path leads to the 14-story, 1000-room, 23,000 square-foot palace. Each day, thousands of pilgrims give the prayer wheels lining the path a clockwise spin as they make their way up to the entrance.

Stunningly dominating the skyline of Lhasa atop the crest of Marpo Ri hill, the seventh-century Potala is considered Lhasa’s most holy destination for a pilgrimage. Winding up the hill, a stone path leads to the 14-story, 1000-room, 23,000 square-foot palace. Each day, thousands of pilgrims give the prayer wheels lining the path a clockwise spin as they make their way up to the entrance.

The Potala is a holy place, but it is also an administrative and political complex. It is comprised of the Red and White Palaces; inside the White Palace are two small sacred chapels, the Phakpa Lhakhang and the Chogyal Drubphuk. The Potala’s most venerated Buddha statue, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, is housed inside the Phapka Lhakhang.

It is believed that Emperor Songtsen Gampo built the Potala as a meditation retreat in the seventh century A.D. Construction of the present palace began in 1645 during the reign of the fifth Dalai Lama. The White Palace ( Potrang Karpo) was completed around 1648 and the Red Palace (Potrang Marpo) was added between 1690 and 1694. Approximately 7000 workers and 1500 artists and craftsmen were enlisted to build the structures. In 1922, the 13th Dalai Lama renovated many of the chapels and assembly halls in the White Palace and added two floors to the Red Palace. In the twenty years after the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1950, the Red Guard decimated many religious buildings; fortunately, the magnificent architecture of the Potala, and all its contents, were spared.

Robert Pryor, Director of Buddhist Studies at Antioch College, points out that “the Buddhists built temples on powerful spots, not unlike the Native Americans. Their places of worship have been used for hundreds of years, and the prayer and chanting allows one to sense the feeling of energy, if one is open to these feelings.”

Robert Pryor, Director of Buddhist Studies at Antioch College, points out that “the Buddhists built temples on powerful spots, not unlike the Native Americans. Their places of worship have been used for hundreds of years, and the prayer and chanting allows one to sense the feeling of energy, if one is open to these feelings.”

Visitors enter the Potala through the dimly lit library. Holy books, hand-printed in the seventh century, are housed in individual glass cubicles. Pilgrims lower their heads under the high bookshelves, hoping to receive the message of the many scriptures and teachings of Buddha.

The pungent smell of candles burning in yak butter and sticks of burning incense combined with a temperature of about 40 F chill and cloud the atmosphere. The palace is unheated and poorly lit. Spillage from the candles makes sections of the stone floor slippery.

As visitors move through the palace, the pilgrims’ low constant Om mani padme hum resonates throughout. Not all of the Potala’s thousand rooms are open to the public, but those that are can easily consume three hours of climbing steep ladders edged by brass and wooden rails, crossing high, worn wooden door transoms, and navigating steep, uneven steps in the dim light.

In each room pilgrims make offerings of yuen (Chinese money), leave colorful prayer flags and clothing, and drape fine white silk scarves (khatas) on Buddha statues of deities and lamas (great teachers in the Buddhist tradition). Most of the statutes are of members of the virtuous Yellow Hat Sect; each is gowned in elegant brocaded robes covered with ornate patterns of turquoise, silver, pearls, and coral.

In each room pilgrims make offerings of yuen (Chinese money), leave colorful prayer flags and clothing, and drape fine white silk scarves (khatas) on Buddha statues of deities and lamas (great teachers in the Buddhist tradition). Most of the statutes are of members of the virtuous Yellow Hat Sect; each is gowned in elegant brocaded robes covered with ornate patterns of turquoise, silver, pearls, and coral.

When the pilgrims have completed their journey, they will head back to their homes or villages. Around Lhasa, colorful prayer flags flutter everywhere: from the tops of homes and buildings, along riverbanks and on mountaintops, blessing all who pass. Om mani padme hum is carved into rocks and written on prayer wheels—worship here such an integral part of daily life that it remains the cultural heart of this small country, still vibrant despite forty years of occupation.

Lhasa: The Heart of Buddhist Tibet

Tibet is best known as the former home of the Dalai Lama, and—since the beginning of the Chinese occupation in the 1950’s—the homeland of hundreds of thousands of exiled or oppressed resident Tibetan Buddhists. While the Tibetan diaspora has become a cause celebré in the West, China has kept the small snowy country mostly closed to outsiders. Until recently, the few who have managed to visit have been mostly climbers attempting to summit Everest (by the less-popular northern route) and lesser-known Himalayan peaks.

Tibet is best known as the former home of the Dalai Lama, and—since the beginning of the Chinese occupation in the 1950’s—the homeland of hundreds of thousands of exiled or oppressed resident Tibetan Buddhists. While the Tibetan diaspora has become a cause celebré in the West, China has kept the small snowy country mostly closed to outsiders. Until recently, the few who have managed to visit have been mostly climbers attempting to summit Everest (by the less-popular northern route) and lesser-known Himalayan peaks.

In the last few years, however, the People’s Republic of China (perhaps bowing to political pressure; perhaps just dazzled by revenue projections) has begun to crack the door open to tourists.

China’s rules for Tibetan entry are strict and, to Western eyes, can seem either offensive or silly (for example, no photograph of the Dalai Lama may enter the country). Visitors must be accompanied by a Chinese tour operator and the most common entry is a flight on China Southwest Airlines from Chengdu, China to the Gonggar airport, 65 miles from Lhasa.

China’s rules for Tibetan entry are strict and, to Western eyes, can seem either offensive or silly (for example, no photograph of the Dalai Lama may enter the country). Visitors must be accompanied by a Chinese tour operator and the most common entry is a flight on China Southwest Airlines from Chengdu, China to the Gonggar airport, 65 miles from Lhasa.

Enduring the restrictions is worth it, however—Tibet has a stark but intoxicating beauty. In my case, the beauty was enhanced by a surreal, disorienting lightheadedness that came over me soon after we arrived in Gonggar (which sits at 12,000 feet above sea level). Was being in the long-forbidden country a reality? I returned to Earth after a dose of Diamox, a prescription drug that alleviates altitude sickness—one pill and a short nap and I was fine.

The road to Lhasa follows the Yarlung River. Our bus trundled toward the capital along the river road, dwarfed by the snow-capped peaks that edge the valley. On the water, fishermen floated along in square yak-skin boats. Everywhere flew Tibetan prayer flags—red (symbolizing fire), white (clouds), yellow (earth), green (water), and blue (sky), inscribed with the mantra Om, mani padme hum (“Om, the jewel in the lotus”). The flags fluttered from hilltops, rock-pile stupas (gravesites), and village rooftops.

The road to Lhasa follows the Yarlung River. Our bus trundled toward the capital along the river road, dwarfed by the snow-capped peaks that edge the valley. On the water, fishermen floated along in square yak-skin boats. Everywhere flew Tibetan prayer flags—red (symbolizing fire), white (clouds), yellow (earth), green (water), and blue (sky), inscribed with the mantra Om, mani padme hum (“Om, the jewel in the lotus”). The flags fluttered from hilltops, rock-pile stupas (gravesites), and village rooftops.

Most of the houses we passed were made of mud and straw, painted a stark white with a single, colorful door adorned with a shiny brass doorknob. Low enclosing walls surrounding each yard were splattered randomly with white paint and dotted with patties of yak or cow dung; when dry, the patties fall to the ground and are used as cooking or heating fuel.

After the colorful countryside, the drab brutalist architecture of Lhasa (a contribution of 1960s Communist China) came as a disappointment. The few trees that lined the streets were no help, having had their branches trimmed down to the trunks. But the city’s beauty is not entirely lost: it emerges in the faces and clothes of the Tibetan people and in the fascinating architecture and décor of the city’s temples and monasteries. The most striking of these is the Potala, the winter palace of the exiled Dalai Lama. The 14-story, 1000-room palace towers over the city, one of the most revered destinations for pilgrims and tourists alike (see sidebar).

Picturesquely perched on a hillside near the outskirts of the city is the Sera Yellow Hat Sect monastery, built in 1416. Here visiting pilgrims placed their heads inside a small altar decorated with an image of Hyagriva, a Buddhist protector. A monk sitting nearby chanted a mantra; the chant is a series of Sanskrit syllables, an utterance thought to create good effects in the minds of oneself or others. The pilgrims first placed their hands together in namaste, the position of prayer, then touched their heads (mind), mouth (speech), and heart.

Picturesquely perched on a hillside near the outskirts of the city is the Sera Yellow Hat Sect monastery, built in 1416. Here visiting pilgrims placed their heads inside a small altar decorated with an image of Hyagriva, a Buddhist protector. A monk sitting nearby chanted a mantra; the chant is a series of Sanskrit syllables, an utterance thought to create good effects in the minds of oneself or others. The pilgrims first placed their hands together in namaste, the position of prayer, then touched their heads (mind), mouth (speech), and heart.

The Sera monastery, home to 400 monks, felt more intimate than the Potala, and visitors are invited see the day-to-day living and working spaces. In a kitchen blackened by dung fire, large pots and copper ladles hung on the wall; a monk offered visitors cups of yak butter tea, a staple of the Tibetan diet. In a nearby courtyard, shouts and hand clapping drew our attention to a ritual debate between many teams of monks. As one young monk sat on the ground, the other clapped and chanted animatedly; we wished that we could get an interpretation of their discussion.

After the monastery, we saw the Jokhang Temple, considered the most sacred temple in Lhasa. In the courtyard outside, pilgrims gathered to prostrate in prayer. While photographs are permitted in the Potala (albeit for a steep fee of $90–$150 per room) and, for a lesser fee, at the Sera Monastery, no photography is allowed inside Jokhang. This is the home of the statutes of the revered Buddha, Shakyamuni. While all Buddhist statutes are magnificently robed in colorful brocade adorned with pearls, turquoise, coral, and silver, solid gold bowls of holy water rest before Shakyamuni as well as offerings of yuen (money) and khatas (scarves) left by pilgrims.

After the monastery, we saw the Jokhang Temple, considered the most sacred temple in Lhasa. In the courtyard outside, pilgrims gathered to prostrate in prayer. While photographs are permitted in the Potala (albeit for a steep fee of $90–$150 per room) and, for a lesser fee, at the Sera Monastery, no photography is allowed inside Jokhang. This is the home of the statutes of the revered Buddha, Shakyamuni. While all Buddhist statutes are magnificently robed in colorful brocade adorned with pearls, turquoise, coral, and silver, solid gold bowls of holy water rest before Shakyamuni as well as offerings of yuen (money) and khatas (scarves) left by pilgrims.

While there are no images of the current Dalai Lama allowed in the country, his presence hangs like a constant, faint rebuke over occupied Tibet. It is perhaps strongest in the Norbulinka, the summer palace, where we saw the rooms where he gave audiences, his assembly hall, gifts of state presented by visiting dignitaries, and even his bedroom. A simple cot-like bed and an antique record player are the basics of the room.

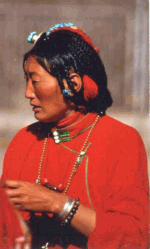

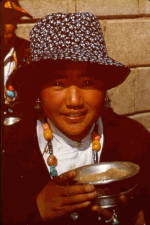

Some in our group visited an unnamed nunnery, where the nuns sew embroidery handicrafts to support their convent. Like the monks, and like the lay Tibetans, the nuns are striking—lithe, handsome people with rosy high-boned cheeks, draped in colorful clothing that seems to sparkle in the thin, bright air. Outside the religious cloisters, Tibetan women adorned their hair with necklaces of turquoise and coral, while men tend to dress in western style

We next turned to the secular, exploring the crowded Borkhor bazaar (market) that surrounds Jokhang Temple. Here hundreds of vendors man crowded stalls, selling everything from prayer flags and prayer wheels to wonderful jewelry, needle and flint cases, and silver purses studded with turquoise and coral. More serious spenders turned their attention to the thick woolen rugs that Tibetans are known for. The Tibet Potala Carpet Company, which offers beautiful wares, is used to dealing with tourists: it ships by air and charges a hefty “merchant services” tax that, a sign explains, is levied by the Chinese government.

Westerners expecting plush accommodations in Lhasa will be disappointed, although reasonably adventurous travelers will do fine at the Lhasa Hotel, base for most tourists. Here each room comes equipped with oxygen bottles for those unused to the altitude. The food, like that at the Hard Yak Café, is also quite basic—most entrées have something to do with yak meat. The locals subsist mainly on tsampa, a barley flour soup, and drink yak butter tea—a bit of an acquired taste for the uninitiated. No one goes to Tibet for deluxe accommodations and gourmet cuisine, but the adventurous, open-minded traveler will be satiated—by the culture and beauty of the Tibetan people.

If you go:

Independent travel is Tibet is difficult. Entry requires a visa permit from the People’s Republic of China. Tour operators include permits in their travel package.

TCS Expeditions by Private Jet (luxury travel) 2025 First Avenue, Suite 450 Seattle WA 98121 800-727-7477 travel@tcs-expeditions.com

Insight Travel (Buddhist pilgrimages) 602 S. High Street Yellow Springs, Ohio, 45387 800-688-9851 www.insight-travel.com info@insight-travel.com

Chengdu Overseas Tourist Corp. 2/F Dongfeng Building, Da Cisis Road Chengdu, Sichuan, China 610061 Fax: (028) 6664611

Tibet Tourism Board: 6/F Peiluomen Laojiefu Building, 233 Nanjing Rd.(E) Huangpu District, Shanghai 200002, P.R of China Tel: 0086-21-33130524 Fax: 0086-21-63231016 www.tibet-tour.com ttbsw@online.sh.cn

Best Time to Travel: The best season for touring in Tibet is from March to October. Those extending their travel beyond Lhasa to higher elevations (Mt. Everest) should plan to visit during summer months.

Altitude: It is important to take time (take a nap) to acclimatize to the 12,000 foot elevation upon arrival. Most flights arrive from Chengdu, China, or Kathmandu, Nepal. Most visitors take Diamox, a prescription used to prevent high mountain altitude sickness. Pace should be slow the first day. Alcoholic beverages are discouraged. It is important to keep the body hydrated. Oxygen is available in most hotel rooms, and tour guides have it readily available. All visitors should talk with a physician prior to visiting Tibet.

Currency: Tibet uses the Yuan, the same monetary system as China. U.S. dollars are accepted by market vendors. The few places that accept MasterCard and Visa charge a 5% additional fee. Travelers checks are not accepted.

Shopping: Hand woven woolen rugs, silver and yak bone prayer wheels, silver purses with turquoise, coral, needle and flint cases, and other handicrafts.

Hotels: Lhasa Hotel, 1 Minzu Rd. (0891) 6832221 FAX (0891) 6835796 Grand Hotel Tibet, Beijing Zhonglu, (0891) 6826096, FAX (0891) 6832195 Tibet Hotel 221 Beijing Rd. (0891) 6834966 FAX (0891) 6836787