September, 2016 Vol. 20, No. 11

Papua New Guinea is the largest tropical island in the world. Inhabited by four million Papuans, Melanesians, Micronesians, and Polynesians, more than 700 distinct dialects are spoken. Located north of Australia, separated by the Coral Sea’s Torres Strait, Papua New Guinea is country of rugged mountains and thick jungles.

Our group gathered in the capitol city of Port Moresby. Adjacent to the airport, the Highlander Hotel was protected from rampant crime by a compound secured with fences, barbed wire, and security guards. The following morning, our small plane landed on a grass strip along the Sepik River in Timbunke village. The houseboat “Sepik Spirit” would be our home for the next several days as we toured in a small flat-bottom jet boats in the Blackwater area.

In native villages, we had an opportunity to purchase artifacts, watch women grind sago palm, a staple of their diet, into pancakes. Palm-floored huts were covered with thatched roofs. Families slept on straw mats covered by mosquito nets. Fires burning next to their mats were used for warmth and cooking.

Seventh-day Adventist missionaries had converted the villagers of Angriman and Mindimbit. School children welcomed us into their classroom in the village of Mumeri. They sat at their hand-carved desks and benches, singing a welcoming song before placing a crown of woven palm and flowers on our heads. Artifacts made by children were primarily penis gourds. In the past these gourds, called horim, were the sole item of clothing worn by the men.

In some villages, natives performed a “sing-sing” for us. Dressed in ceremonial costume, the men and women danced to the music of handmade flutes.

The Karawari region of the Sepik River is typified by rainforest vegetation, a change from wild cane bordering the middle Sepik. Delayed by boat mechanical problems, we only had time to visit the village of Kundamin. When we arrived the women were cooking sago palm. The gluey starch is hard to stir and tasteless in flavor. Leaf vegetables and the protein larvae of the Capricorn beetle, better known as grubs, provide some variety to their diet.

Karawari Lodge has the appearance of a haus Tambaran or Spirit House. A large gable mask hangs at its entrance, which overlooks a beautiful rainforest valley. Birds are abundant, along with geckos and colorful insects. The rooms at the lodge were thatched-roof huts, beds were covered with mosquito netting.

After crawling out of our mosquito netting before daybreak, we learned by radio message that our chartered plane to Mount Hagen had been grounded by fog. Two hours later we climbed 10-foot embankment from the Sepik River to reach a 2400-foot grass runway where we boarded the airplane.

Women sold bilums displayed behind the barbed wire fence of the Mount Hagen airport. Once woven from palm bark, many bilums are now made from colorful Hong Kong yarn. They are knotted on top of women’s head and used to carry children and other burden.

Before leaving Hagen for the coastal city of Madang, we visited the public market. While viewing the variety of fruits, vegetable and different wares, we spotted a man selling ceremonial headbands made from scarab beetles woven with orchid leaves.

Madang is known as the garden spot of Papua New Guinea. We spent two nights at Malolo Plantation, which overlooks the Bismarck Sea. Day trips included the fishing villages of Marut and Lusik. We hiked a beach surrounded by betel nut palms,breadfruit, boxwood, pandanus, and other exotic nut and flower trees. The hands and feet of Didol, the “big man” or village chief, had been ravaged by leprosy.

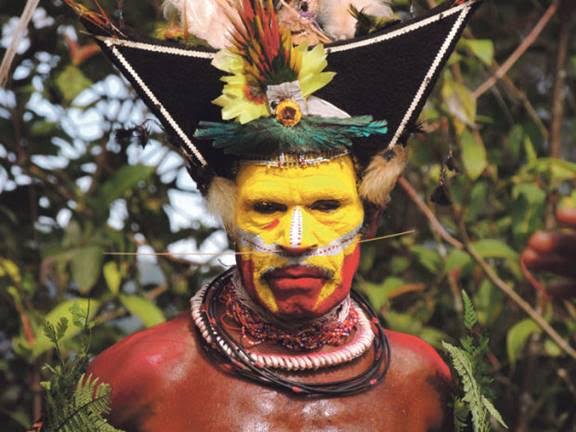

Departing Madang, we flew to Tari in the Southern Highlands. Colorful Huli tribes inhabit this region. The men wear colorful headdresses of cuscus (possum) fur with bird of paradise feathers or headpieces made from their own hair. A hornbill beak necklace is worn on their backs. The Huli continue to have battles and remain one of the most primitive of the tribes of Papua New Guinea.

Huli battles or “paybacks” are somewhat civilized. The warring clans may determine a day to fight and a time to stop for lunch. Women and children are seldom killed. They do not seem to care when tourists watch them fight. Several times we saw warriors guarding clan borders. Some warriors held bow and arrow while others carried homemade guns. Some wore plastic helmets while others wore leafy headdress.

Ambua Lodge, located about 45-minutes from the airport, provided an opportunity to observe a Huli tradition. Pigs were staked along the road during a bride-price negotiation. The ceremony can take several hours or days depending on the value of the bride, her age and the wealth of her family. Wealth is measured by the number of pigs owned by the family. The pig is so revered in Papua, its image is on the $10 dollar kina.

Another day, we passed a man preparing to take a painted skull of his father into his hut. Papua New Guinea is a misogynous society. Deceased women are buried when they die, while men rest above the ground for five years. When the skin has dried and dropped from the bones, the skull is painted, and placed in the hut of the son.

We had been told that two weeks prior to our arrival, a warrior named Andrew had been killed. Payback or another battle was expected in the next several days. The Ambua Lodge is located between two warring Huli clans, the Jawali who lived in the valley, and the Huwale Pu, who lived in the highlands.

At the crack of dawn, I awoke to the cry of a warrior in the valley. Was he calling his pigs or was this a battle cry? In the village of Wapia, we observed a “sing-sing,” in Boronapa village, the Huli demonstrated the making of fire by rubbing two pieces of cane with a cord. After an impressive bow and arrow shooting demonstration, we visited the women’s side of the village to see the huts of pigs.

Men and women, who do not sleep together, typically have sex in the garden for the purpose of reproduction. Many times pigs share the women’s hut. The role of a women is to tend gardens, raise children, and carry burden in their bilums. Men do the hunting and cooking. Men believe that women are capable of casting spells and sometimes carry evil spirits. They are especially afraid of seeing women during menstrual cycles, so during this period, women stay in a separate hut.

One afternoon, we had the opportunity to go bird watching. Papua New Guinea is known for its spectacular Birds of Paradise. We were fortunate to observe the King of Saxony, Crested bird of paradise, several Princess Stephanie astrapia, a ribbon-tail astrapia with its long white tailfeathers, a sicklebill, and a king parrot. The 24-inch tail feather of the King of Saxony is often worn in the Huli headdress. Observing these rare, magnificent birds makes the country a birdwatcher’s dream. There are also wonderful varieties of insects and beetles. Insects thriving in the jungle include the large rhinoceros beetle with its unique beak.

On our final day in Tari, we visited the bachelor village of Kaka. Huli boys enter the village at sixteen to learn the traditions of their tribe. During their eighteen-month stay, they grow their hair to use for their own “wigman” headdress. The human hair wig is then adorned with daisies and bird of paradise feathers. While they are learning Huli rituals and traditions, the young men cannot leave the compound or look at a woman. Their role is to maintain the grounds and tend the gardens. They are presented a carved diploma at graduation, which they will displayed with pride next to the door of their hut.

The opportunity to meet with Pajia, a witchdoctor, was an experience shared by only a few visitors. Pajia hid from missionaries for twenty years to avoid conversion from his religious practices. When we saw him, he had not received foreign visitors for three years. With the help of an interpreter, Pajia showed us how he made knives from bamboo. He demonstrated his use of axes, bows and arrows. He took us to his magic garden where he showed us his medicinal powers. Rubbing my son Jeffrey’s hands with a nettle leaf, he created a painful burning sensation. He then rubbed Jeffrey’s hand with a ginger leaf. The pain subsided in about ten minutes.

The nettle leaf is used prior to the scarification initiation ritual to prepare men for the pain they will endure during the ceremony. A compound mixture of clay, burnt lime and tigaso tree oil is put into self-induced wounds to create permanent scars that look like tattooing.

Pajia also took us to his graveyard. His demeanor showed great respect, his eyes were cast downward as he showed us the skull of his father. We walked through the graveyard to his “magic place,” the burial site of his witch doctor ancestors. Located in a sexually symbolic, “Georgia O’Keefe-ish” rock outcropping, were the painted skulls of his male ancestors dating back nine generations. Pajia’s magic stones were also resting in this outcropping.

At the time of our visit, the remoteness of the region has resulted in fewer missionary conversions. The Huli tribe is frequently seen wearing traditional dress. Their faces are painted, and they wear bird of paradise feathers or fern headdresses, lap-lap skirts and some pierce their noses with bones. Sometimes they giggled when they saw us and wanted to touch our hands.

The culmination of our visit was two days at the Mt. Hagen sing-sing. Approximately fifty tribes danced and sang in ceremonial costumes. Many tourists take this opportunity to watch the festivities held for prize money. Locals watched the dancing and singing behind a barbed wire fenced surrounding the field, while tourists sat in a concrete grandstand. The more recognizable of the tribes were the Huli, Mudmen, and Morabe.

Twelve of us had shared a two-week adventure of a lifetime. We said farewell to Papua New Guinea in pidgin, “lookim yu behind.”

www.pngtravel.com