Text and photos by Mary L. Peachin

November, 2016, Volume 21, No. 2

Colorfully dressed, her red babushka contrasted with a plaid shirt covered by a yellow rubber apron and rubber boots. Scooping herring from a long tray, she inhaled a cigarette as she quickly fileted, salted, and tossed each herring into a barrel. Paid by the barrel, time was of the upmost importance.

Norwegians taught Icelanders the technique of fishing and salting herring. During the brief summer fishing season, “herring girls” would work thirty hour shifts. The men, who did the fishing, might have to wait anywhere from a few hours to several days to unload their catch. The fish were then separated by freshness and size to determine whether they would be used as food or made into meal or fish oil.

For each barrel, the girls tucked a token into their boots. At the end of the week, on pay day, tokens were converted to króna. When they took time off, the evenings were spent drinking and dancing with the fishermen. “It was a short season with no time to rest. We had all winter to catch up on our sleep.”

The building behind them housed a dormitory where the girls shared multi- level bunks. They had a shared bath and small kitchen.

The building behind them housed a dormitory where the girls shared multi- level bunks. They had a shared bath and small kitchen.

An adjacent building was used to process the fish while a third housed fishing boats during the winter months. In spite of many warnings of over fishing, Iceland, Norway, and Russia continued to fish the herring until they eliminated the industry in 1968.

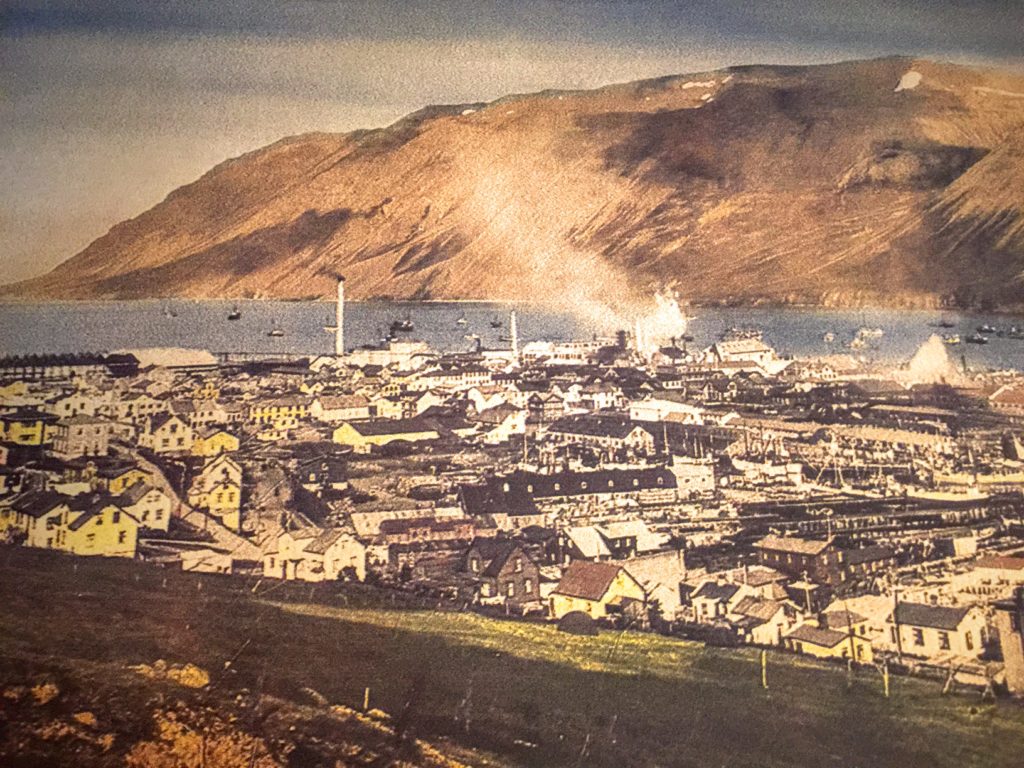

Many towns, villages and areas along the north and east coast of Iceland were deeply affected by the arrival of herring fishing, but nowhere did the herring industry have an impact as large as Siglufjörður. During the summer of 1903, Norwegian fishermen arrived sailing on herring vessels. In four decades, the small village was transformed into a thriving town of more than three thousand inhabitants with twenty-three salting stations and five reduction factories.

Many towns, villages and areas along the north and east coast of Iceland were deeply affected by the arrival of herring fishing, but nowhere did the herring industry have an impact as large as Siglufjörður. During the summer of 1903, Norwegian fishermen arrived sailing on herring vessels. In four decades, the small village was transformed into a thriving town of more than three thousand inhabitants with twenty-three salting stations and five reduction factories.

As the herring industry grew, a gold rush-like atmosphere lead to Siglufjörður been dubbed the “Atlantic Klondike.” The town became a magnet for herring speculators who came and went, some making a lot of money during the boom. Siglufjörður became a mecca for tens of thousands of workers.

When storms arrived, the fjord’s sheltered waters contained a massed fleet of hundreds of herring ships. Siglufjörður’s streets were congested with crowds and activities resembling those of major cities.

When storms arrived, the fjord’s sheltered waters contained a massed fleet of hundreds of herring ships. Siglufjörður’s streets were congested with crowds and activities resembling those of major cities.

As Icelandic pioneers developed new and more efficient fishing technology, the instability of herring stock was strongly impacted. As early as 1950, the catch began to decline.

In 1989, local volunteers spent five years renovating the Róaldsbrakki building to create a three building Museum to recognize Siglufjörður’s herring industry: Róaldsbrakki, Grána and The Boathouse.

In 1989, local volunteers spent five years renovating the Róaldsbrakki building to create a three building Museum to recognize Siglufjörður’s herring industry: Róaldsbrakki, Grána and The Boathouse.

Róaldsbrakki, the original 1907 Norwegian salting station, exhibits history. A display of artifacts and photographs detail 1940 Siglufjörður when thousands of people arrived each herring season in search of a well-paid job including the herring girls, fishermen and other workers. Hundreds of herring girls, who arrived from around the country, were housed at the station. The upper floor living quarters remain untouched.

Grána, a herring factory built in the 1930s, displays the process of reduction of herring into meal and oil. Machinery gathered from old, abandoned herring factories, including Ingólfsfjörður and Hjalteyri, have made the exhibit appear like the original factory.

The Boathouse, the newest building, was opened by Crown Prince Håkon of Norway in 2004. An example of the town‘s bustling harbour has been recreated.

Today’s salting demonstrations provides visitors the opportunity to share an historic time when herring girls salted and packed herring into barrels while smoking cigarettes and gossiping about handsome fishermen. An accordion player adds to creating the atmosphere when Siglufjörður served as the center of Iceland’s herring fisheries.