Mar 2000, Vol. 4 No. 6

In the winter of 1925, an outbreak of diphtheria threatened the population of the snowbound city of Nome, Alaska. The native Inuits, exposed to a higher risk of the disease because of years of isolation, were in a potential life-threatening situation. It took 127 hours and 20 teams of dog mushers to relay lifesaving vaccination serum to Nome.

In the winter of 1925, an outbreak of diphtheria threatened the population of the snowbound city of Nome, Alaska. The native Inuits, exposed to a higher risk of the disease because of years of isolation, were in a potential life-threatening situation. It took 127 hours and 20 teams of dog mushers to relay lifesaving vaccination serum to Nome.

In 1973, the 1049-mile Iditarod trail dog sled race, to commemorate this heroic effort, was begun. Mushers challenged the hazardous trail over frozen tundra, sometimes in blizzard conditions. Jerry Austin is one of those mushers, and a member of the Iditarod Hall of Fame.

Today, Jerry leads dogsledding adventures, giving his clients a “taste” of the Iditarod, without the hardship. As we “mushed” our dog team onto the ice of St. Michael’s Bay, south of Nome, five of us, each with a veteran five-dog team sled, excitedly followed Jerry Austin as he led us on this 100-mile six-day tour.

Our route followed an historic Russian trading route used by the local Inuits. The landscape of the tundra was windswept making the trail crusty and fast. To maintain control on curves and descent, I was heavy on the foot brake, a metal bar with two metal projections. When lead dogs, Mac and Trixie veered right and the sled continued straight, I stomped on the brake. Those dogs could read my fear.

Our route followed an historic Russian trading route used by the local Inuits. The landscape of the tundra was windswept making the trail crusty and fast. To maintain control on curves and descent, I was heavy on the foot brake, a metal bar with two metal projections. When lead dogs, Mac and Trixie veered right and the sled continued straight, I stomped on the brake. Those dogs could read my fear.

Jerry cautioned us to keep control of the sled. “Never let go of the sled. If necessary, plow the snow with your face. If the dogs were to strand you in a blizzard, you could die. In good weather you’ll chase the sled for hours.”

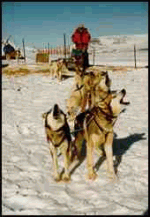

Our teams were a mixed hybrid called “village dog.” They averaged about knee-high and weighed between 35 to 50 pounds. They could pull the sled a mile in three minutes and run at a pace of 17 m.p.h. Other mushing breeds include the Siberian husky, Alaskan malamute, Japanese Akita, Norwegian elkhound, and Finnish Spitz.

As we followed a gentle trail along the coastal plain, we bumped along at a pace of approximately 10 m.p.h. Outfitted in boots, bib-type overalls, hooded fur-trimmed parkas, and mittens (all of which were insulated), we hit the trail on a balmy day, clear and sunny Arctic. In a few days, we would be grateful to be wearing this “survival gear.”

As we followed a gentle trail along the coastal plain, we bumped along at a pace of approximately 10 m.p.h. Outfitted in boots, bib-type overalls, hooded fur-trimmed parkas, and mittens (all of which were insulated), we hit the trail on a balmy day, clear and sunny Arctic. In a few days, we would be grateful to be wearing this “survival gear.”

After a few hours on the trail, we stopped to take a break. Carefully setting two metal snowhooks on both sides of the sled, I set another front hook to keep the dogs on a taught line. We fed the dogs a real gourmet treat of frozen salmon chunks. Within two minutes the dogs were yapping and leaping, eager to again hit the trail.

Each time we stopped, Jerry Austin examined the condition of each dog. He did so by checking the size of their esophagus. An enlarged opening is symptomatic of overheating. If this happened, Jerry would cool the dog in a snow bank.

Klikitarik was our first campsite. The small inlet was once used by the Inuits to store frozen beluga whales. The campsite had two heated metal Quonset huts, one used for sleeping, the second for eating. As we ate caribou roast for dinner, Jerry shared some historical stories about the early inhabitants of the area.

Klikitarik was our first campsite. The small inlet was once used by the Inuits to store frozen beluga whales. The campsite had two heated metal Quonset huts, one used for sleeping, the second for eating. As we ate caribou roast for dinner, Jerry shared some historical stories about the early inhabitants of the area.

Before crawling into my sleeping bag, I said goodnight to my dogs. We had bonded. I wondered if they knew I felt my life was dependent on them.

The next morning, we harnessed the eager, barking dogs for a 25-mile run to to a fishing camp on the Golsovia River. As we headed up the six-mile trail in the Toik Hills, we could see the Unalakeet Mountains and the Coastal Range. We searched for herds of caribou and musk ox, native to the slopes of these mountains. While we were also in black bear and grizzly country, we weren’t eager for a “bear encounter.”

In the late afternoon, we arrived at the Golsovia River Lodge. We looked forward to a two-day layover in the hand-built (by Jerry) lodgepole lodge. The sleeping platform accommodated 20 people, a generator supplied electricity for warmth and cooking.

In the late afternoon, we arrived at the Golsovia River Lodge. We looked forward to a two-day layover in the hand-built (by Jerry) lodgepole lodge. The sleeping platform accommodated 20 people, a generator supplied electricity for warmth and cooking.

The lodge was located at the edge of the ice-covered Bering Sea. We took the day to hike inland along the Golsovia River. The following day a venture onto the sea ice ended abruptly when we spotted a human-hand size footprint, and it was only a polar bear cub.

The barometer had dropped during our two days of rest. Jerry predicted stormy weather. for our return trip. As the temperature hovered at zero, the wind chill was minus-ten below. The dogs loved this frigid running weather, we were more grateful for the “survival gear.”

After arriving safely back in Klikitarik, the snow continued to fall for twelve hours. The next morning, the dogs, curled with their noses tucked to their tails, looked like sugar-dusted doughnuts. They leapt, yelped and pranced. They knew they were headed back to their kennels in St. Michael.

After arriving safely back in Klikitarik, the snow continued to fall for twelve hours. The next morning, the dogs, curled with their noses tucked to their tails, looked like sugar-dusted doughnuts. They leapt, yelped and pranced. They knew they were headed back to their kennels in St. Michael.

The weather continued to deteriorate throughout the day until we were in whiteout conditions. Visibility was near zero, the sky, sea ice, and low inland mountains were indiscernible. The horizon had disappeared.

As we crossed the three and a half-mile ice-covered water of St. Michael’s bay, the dogs were in control. Our lives were dependent on their uncanny skills of finding their way home. We trusted them to not get lost.

We saluted and praised our dog teams as we glided into town. We may have been lost, but it was just another day on the Alaskan Arctic for the dogs.