Jul 2002, Vol. 6 No. 9

Discovering a Caribbean Island destination that offers superb scuba diving plus game fishing is not easy as one might think. The two sports don’t always blend, and are not always available at the same resort. Many an angler has surrendered a hooked fish to the hungry jaws of a shark. After that bloody experience, the fisher can’t imagine descending into the ocean depths. Meanwhile, divers tend to feel that anglers are “meat hunters” not realizing that the majority of them release caught fish unharmed. The outcome of my web surfing found a destination offering both; plus it didn’t require crossing multiple time zones or the crossing the international dateline. To fill days with both diving and fishing I headed to the Southern Cross Club on Little Cayman Island, the smallest of the Caymans.

Discovering a Caribbean Island destination that offers superb scuba diving plus game fishing is not easy as one might think. The two sports don’t always blend, and are not always available at the same resort. Many an angler has surrendered a hooked fish to the hungry jaws of a shark. After that bloody experience, the fisher can’t imagine descending into the ocean depths. Meanwhile, divers tend to feel that anglers are “meat hunters” not realizing that the majority of them release caught fish unharmed. The outcome of my web surfing found a destination offering both; plus it didn’t require crossing multiple time zones or the crossing the international dateline. To fill days with both diving and fishing I headed to the Southern Cross Club on Little Cayman Island, the smallest of the Caymans.

The 12-bungalows of the intimate beach resort was originally owned by a group of anglers. In 1991, the Club was purchased by the Hillenbrand family, who opened it to the public, and took advantage of the increasing popularity of Cayman diving by catering to both divers and anglers.

The 12-bungalows of the intimate beach resort was originally owned by a group of anglers. In 1991, the Club was purchased by the Hillenbrand family, who opened it to the public, and took advantage of the increasing popularity of Cayman diving by catering to both divers and anglers.

Little Cayman’s amenities will suit any ocean lover. You can toss a coin trying to decide which is better. Diving the world famous walls of Bloody Bay and Jackson Marine Park, or stalking elusive bonefish in the flats along the shore of the island. It is all in a day’s fun; a two-tank dive morning, a break for lunch, an afternoon of fishing.

Seasonal tradewinds dictate spring activities on the island of Little Cayman. Blowing winds create turbulence and strong currents making it unsafe for dive boats to navigate around the western tip to reach Little Cayman’s coveted north-side Bloody Bay wall dive site (so named for the thousands of turtles slaughtered there many years ago.) When the wind shifts, the opposite is true, it’s rough on the south coast, where most of the island’s half dozen resorts are located, and the north side is calm. Getting to Bloody Bay and Jackson can require a grueling 40-minute boat ride, especially through the cut in the coral reef to the ocean, a 30-foot wide channel.

Seasonal tradewinds dictate spring activities on the island of Little Cayman. Blowing winds create turbulence and strong currents making it unsafe for dive boats to navigate around the western tip to reach Little Cayman’s coveted north-side Bloody Bay wall dive site (so named for the thousands of turtles slaughtered there many years ago.) When the wind shifts, the opposite is true, it’s rough on the south coast, where most of the island’s half dozen resorts are located, and the north side is calm. Getting to Bloody Bay and Jackson can require a grueling 40-minute boat ride, especially through the cut in the coral reef to the ocean, a 30-foot wide channel.

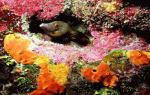

The magic of Bloody Bay wall is the shallowness of the reef wall, which begins in 18 feet of water and descends into the abyss of the Cayman trough, a depth estimated at 6000-feet. The coral and fish life is healthy and untouched, the visibility unlimited. Further east, Jackson Marine Park descends more gradually. Pinnacles of coral outcroppings, sandy slopes, and underwater canyons with numerous tunnels open onto the ledge of the depthless wall.

The magic of Bloody Bay wall is the shallowness of the reef wall, which begins in 18 feet of water and descends into the abyss of the Cayman trough, a depth estimated at 6000-feet. The coral and fish life is healthy and untouched, the visibility unlimited. Further east, Jackson Marine Park descends more gradually. Pinnacles of coral outcroppings, sandy slopes, and underwater canyons with numerous tunnels open onto the ledge of the depthless wall.

A barracuda drifts lazily in the gentle current. Nassau groupers snuggle among the rocks. Lobsters, usually holed up during the day, were lumbering over rocks in search of a new hole or mate, or both. Tiny garden eels appear like miniature cobras swaying from holes in the sandy bottom they share with a variety of rare blennies and gobies. One of many queen conch etches a track in the sand.

Divemaster Guy Chaumette yarns tales of pirates the likes of Captain Morgan. At a dive site named Donna’s Delight, he tells of the Captain’s affair with Lady Donna. Leading us through tunnels in Jackson Bay, Guy hoped to show us how to gently pet a Nassau grouper (only if they approached the diver.) Nassau and eel fish together in a symbiotic relationship, and occasionally associate a diver poking in holes as a potential food finder. We didn’t spot any friendly groupers, but did see beautiful black and white-striped juvenile spotted drum, and some frilly lettuce leaf sea slugs. Other sites we dived included Mixing Bowl and Barracuda Bight (not bite), Lea Lea’s Lookout, and Cascade, a site where the sandy slope was like snowy white powder. Guy said it should have been named “ski slope.” We were hoping to see some “big stuff” cruising the wall. In his briefing, so as not to “jinx” the opportunity, Guy jokingly substituted the words “roosters and seagulls” for mantas and sharks. Unfortunately none of the above were sighted. Northeastern winds returned and again the dive boats were forced to stay on the south shore.

Divemaster Guy Chaumette yarns tales of pirates the likes of Captain Morgan. At a dive site named Donna’s Delight, he tells of the Captain’s affair with Lady Donna. Leading us through tunnels in Jackson Bay, Guy hoped to show us how to gently pet a Nassau grouper (only if they approached the diver.) Nassau and eel fish together in a symbiotic relationship, and occasionally associate a diver poking in holes as a potential food finder. We didn’t spot any friendly groupers, but did see beautiful black and white-striped juvenile spotted drum, and some frilly lettuce leaf sea slugs. Other sites we dived included Mixing Bowl and Barracuda Bight (not bite), Lea Lea’s Lookout, and Cascade, a site where the sandy slope was like snowy white powder. Guy said it should have been named “ski slope.” We were hoping to see some “big stuff” cruising the wall. In his briefing, so as not to “jinx” the opportunity, Guy jokingly substituted the words “roosters and seagulls” for mantas and sharks. Unfortunately none of the above were sighted. Northeastern winds returned and again the dive boats were forced to stay on the south shore.

Here the wall begins in depths of 75-feet or more. At Windsock ( a site named because its proximity to the island’s grass air strip), we swam through a tunnel that opened on the wall at 109 feet A second shallower dive dropped us on the Soto Trader, a barge that sank in the late 1970’s. There was an explosion aboard while the ship was delivering food supplies to the island. Divemaster Hugh Evans, a “macro-maven” found a rare pipehorse, smaller and whispery than its relative, the seahorse. He terminated one dive near a perfect specimen of pillar coral.

“Anything over none is a bonus” fishing guide Dennis Evenson said as he poled the 19-foot skiff quietly over the shallows of South Sound Hole. We scanned the bay for chalky water indicating “mudding”—or feeding bonefish, the wary “grey ghost of the flats.” The fish feed among patches of eelgrass in aquamarine flats shored by aerial roots of red and white mangroves. A school of white egrets soared above us as we motored past Owen’s Island. A fluffy Maryland tern chick chirped at his mom for some food on a dock.

“Anything over none is a bonus” fishing guide Dennis Evenson said as he poled the 19-foot skiff quietly over the shallows of South Sound Hole. We scanned the bay for chalky water indicating “mudding”—or feeding bonefish, the wary “grey ghost of the flats.” The fish feed among patches of eelgrass in aquamarine flats shored by aerial roots of red and white mangroves. A school of white egrets soared above us as we motored past Owen’s Island. A fluffy Maryland tern chick chirped at his mom for some food on a dock.

The key to our fishing success can be credited to the circle hooks we used. Bonefish are skittish, elusive, high power runners who strip line like crazy as they lip-hooked themselves on the barbless hooks. Occasionally a shark or barracuda cut the leaderless line, and once in awhile we release a mutton snapper or yellowjack. For two days the wind blew at 25 knots or more, too stiff to cast even a spinning reel. When it calmed, Dennis felt as though I had “graduated” from blind casting. We headed to the north side of the island to wade and stalk the elusive bonefish along coral crusted shores broken by patches of turtle grass. Driving a pickup to the other side of the mile wide island Dennis pointed out the “tourist tree”, he didn’t know the name of the species, but noted that it was “red and peeling” like a sunburned tourist. The few vehicles on the road yield the right of way to soldier or hermit crabs when they cross the road to dine on wild fig trees. Wild cotton, jasmine, and sea grapes lined the roadway.

The key to our fishing success can be credited to the circle hooks we used. Bonefish are skittish, elusive, high power runners who strip line like crazy as they lip-hooked themselves on the barbless hooks. Occasionally a shark or barracuda cut the leaderless line, and once in awhile we release a mutton snapper or yellowjack. For two days the wind blew at 25 knots or more, too stiff to cast even a spinning reel. When it calmed, Dennis felt as though I had “graduated” from blind casting. We headed to the north side of the island to wade and stalk the elusive bonefish along coral crusted shores broken by patches of turtle grass. Driving a pickup to the other side of the mile wide island Dennis pointed out the “tourist tree”, he didn’t know the name of the species, but noted that it was “red and peeling” like a sunburned tourist. The few vehicles on the road yield the right of way to soldier or hermit crabs when they cross the road to dine on wild fig trees. Wild cotton, jasmine, and sea grapes lined the roadway.

Wading on razor sharp coral pocked with spiny sea urchins, we searched for tailing fish feeding in the grass. “Bone fish like low water while permit (another highly sought after game fish) like high tide,” Dennis commented as we waded along the shallows. It was difficult stalking, and again too windy to throw a fly rod. I got lucky on my first cast, but so did the bonefish that was chased into shore by a hungry barracuda. The barracuda fled at the sight of our feet just as I yanked the bonefish out of its grasp. The bloody scrap on its tail probably meant its demise.

Wading on razor sharp coral pocked with spiny sea urchins, we searched for tailing fish feeding in the grass. “Bone fish like low water while permit (another highly sought after game fish) like high tide,” Dennis commented as we waded along the shallows. It was difficult stalking, and again too windy to throw a fly rod. I got lucky on my first cast, but so did the bonefish that was chased into shore by a hungry barracuda. The barracuda fled at the sight of our feet just as I yanked the bonefish out of its grasp. The bloody scrap on its tail probably meant its demise.

“Now you’re bonefishing” Dennis said as he gave me a “high five”. I admire anglers with the determination to stalk rocky shores to throw a fly at these spooky, speedy (25-30 mph compared to a trout that swims at 5- mph) fish. When guests call the resort asking what gear to bring, Dennis always tells them not to worry, just “practice and practice and practice and then practice some more, throw until your casting can be directed to these ‘target’ fish.” My next challenge was to release a bone on a fly rod and when the winds subsided, I gave it a try. The instinct to pull back the rod to “hook” the fish cost two broken lines, but the Thundercreek fly (made locally and specifically for bonefish) succeeded in attracting another bonefish. As the reel screamed, the fish stripped the line to its Dacron backing. I felt a real sense of accomplishment when I finally brought the fish to the boat. Another afternoon we got more adventurous and attempted to use squid and minnow imitation dry flies (which float on the surface). The bonefish, too savvy to take the flies, did make a few passes as they arrogantly smacked the flies with their tails.

Before sunrise, we drove the pickup truck to a setting resembling Jurassic Park. A boardwalk leads to Tarpon Lake, one of the few landlocked settings for this magnificent fighting fish. A spider web, its web strung like a rope across the boardwalk, stopped me in my tracks. Unable to see, I ducked down and passed under it. At the end of the dock the Southern Cross Club caches a small rowboat. The lake, surrounded by dead mangrove trees, smelled of sulfur from rotting roots. A specious of minnows survives as food for the tarpon. The window for catching these fish known as the “silver king” is the half-hour before dawn. Tarpon rolled and snapped as they fed on the minnows, and not my fly. As we approach the spider web on the dock leading back to the pick up, I saw the spider–a huge golden orb.

Before sunrise, we drove the pickup truck to a setting resembling Jurassic Park. A boardwalk leads to Tarpon Lake, one of the few landlocked settings for this magnificent fighting fish. A spider web, its web strung like a rope across the boardwalk, stopped me in my tracks. Unable to see, I ducked down and passed under it. At the end of the dock the Southern Cross Club caches a small rowboat. The lake, surrounded by dead mangrove trees, smelled of sulfur from rotting roots. A specious of minnows survives as food for the tarpon. The window for catching these fish known as the “silver king” is the half-hour before dawn. Tarpon rolled and snapped as they fed on the minnows, and not my fly. As we approach the spider web on the dock leading back to the pick up, I saw the spider–a huge golden orb.

The three tropical Caribbean islands, located south of Cuba have a fascinating history that can be traced back to the 1500’s. Explorer Sir Francis Drake hoisted sail after two days of observing only crocodiles, alligators, and iguanas. Christopher Columbus discovered and named the islands “Las Tortugas” in 1503. In 1655, England colonized the islands of Jamaica and Cayman. The islands were uninhabited until 1700. Half of the 400 residents were slaves picking cotton. During this period of Caymanian history, infamous pirates sailed the surrounding seas. When the slaves were freed in the 1800’s, many chose to remain on the island earning their livelihood as fishermen. Cayman ceased being a dependency of Jamaica in 1962. Today it is an overseas dependent territory of the United Kingdom.

The three tropical Caribbean islands, located south of Cuba have a fascinating history that can be traced back to the 1500’s. Explorer Sir Francis Drake hoisted sail after two days of observing only crocodiles, alligators, and iguanas. Christopher Columbus discovered and named the islands “Las Tortugas” in 1503. In 1655, England colonized the islands of Jamaica and Cayman. The islands were uninhabited until 1700. Half of the 400 residents were slaves picking cotton. During this period of Caymanian history, infamous pirates sailed the surrounding seas. When the slaves were freed in the 1800’s, many chose to remain on the island earning their livelihood as fishermen. Cayman ceased being a dependency of Jamaica in 1962. Today it is an overseas dependent territory of the United Kingdom.

Little Cayman, a tiny spit (population 125-150) of an island, rises 40 feet above sea level. The island, considered part of the British West Indies, is 10-miles long and a mile wide. Bicycles, more than cars pedal the length of the island on its single road. Moving along on the British (left side) of the two-lane road most of the vehicular traffic transports scuba divers or anglers to the handful of resorts along the beachfront. This is an island where the Rock iguana, a sub species of the Cuban variety has the right of way. The extinct Grand Cayman parrot, wiped out in a 1932 hurricane, remains the national bird. The Marine Conservation law, which limits the taking of 20 conch by each boat, protects an abundant species of conch in the Caymans. Its meat is regarded as a cuisine delicacy. New conch legislation is being proposed to reduce limits and establish a closed season. Palm (Royal, silver thatch, bull, and coconut) trees flutter in the tradewinds. The Mexican fruit and Velvety Free-tailed bats treat themselves to the nuts of Indian almond trees while they keep the mosquito population at bay. The banded curly-tailed ironshore lizard does bug patrol on the front porches of the cottages at Southern Cross Club.

Little Cayman, a tiny spit (population 125-150) of an island, rises 40 feet above sea level. The island, considered part of the British West Indies, is 10-miles long and a mile wide. Bicycles, more than cars pedal the length of the island on its single road. Moving along on the British (left side) of the two-lane road most of the vehicular traffic transports scuba divers or anglers to the handful of resorts along the beachfront. This is an island where the Rock iguana, a sub species of the Cuban variety has the right of way. The extinct Grand Cayman parrot, wiped out in a 1932 hurricane, remains the national bird. The Marine Conservation law, which limits the taking of 20 conch by each boat, protects an abundant species of conch in the Caymans. Its meat is regarded as a cuisine delicacy. New conch legislation is being proposed to reduce limits and establish a closed season. Palm (Royal, silver thatch, bull, and coconut) trees flutter in the tradewinds. The Mexican fruit and Velvety Free-tailed bats treat themselves to the nuts of Indian almond trees while they keep the mosquito population at bay. The banded curly-tailed ironshore lizard does bug patrol on the front porches of the cottages at Southern Cross Club.

Little Cayman may be smaller in size and population than its sister island Grand Cayman and Cayman Brac, but its diving and fishing makes it huge. And the quiet, well sometimes the trade winds blow.

If you go:

Cayman Islands Department of Tourism (800) 346-3313 or go to www.divecayman.ky

Southern Cross Club (800) 889-2582 or go to www.southerncrossclub.com