May 2003, Vol. 7 No. 8

“Welcome to the land where men dream in stone.” The turbaned stationmaster greeted us with these words as we walked through Jaisalmer’s railway station. Now, three days later, watching the sunrise set the sandstone facets of this desert outpost aglow, they come back to us.

“Welcome to the land where men dream in stone.” The turbaned stationmaster greeted us with these words as we walked through Jaisalmer’s railway station. Now, three days later, watching the sunrise set the sandstone facets of this desert outpost aglow, they come back to us.

We are sitting on the shore of the water reservoir below the town of Jaisalmer, our backs against the stone railing of a Hindu temple. Behind us, a man chants softly as he sweeps among the shrines, and somewhere across the desert a camel bell fades into silence. The first rays of dawn catch on the peak of the palace, then the pointed Jain temples, watchtowers and crenellated ramparts of the hilltop fortress. Finally, temples, arches and cupolas along the shoreline, all of carved yellow sandstone, gleam like a golden mirage.

The chanting stops and the chanter, Mahesh Maheshwari, politely introduces himself. He is a textile merchant in town. Maheshwari’s family has lived here, he tells us in fine English, for 500 years. Tidying up the Sita Durga temple each day before opening his shop is a labor of love. “Our prince used to come to these temples every morning with his attendants to pray. See how the stones of the fort and temples shine? In the morning time like this, you see why we call Jaisalmer the Golden City.”

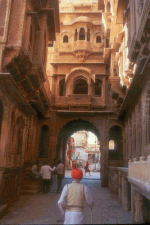

To spend a few days here in the far northwestern part of India, in a converted caravansary or haveli (merchant house) inside the hilltop fortress, or in the old walled town below, is to find yourself back in the world of “Arabian Nights.” No automobiles are allowed in the old town and not even camel carts are permitted within the fortress gates. Centuries-old bazaars offer wonderfully exotic Rajasthani handicrafts, and the surrounding desert contains oases where peacocks strut and camels roll in the sand. Not least of all, the touts and tourists often encountered elsewhere in the state of Rajasthan–India’s most visited destination after the Taj Mahal–stop in Jodhpur, 180 miles to the east. Jaisalmer (population 30,000) is a joy.

It sits like an exotic islet in the heart of the Thar Desert, 500 miles southwest of Delhi. Everything from the 12th century hilltop fortress to the walled town below the ramparts is fashioned of yellow sandstone. Craftsmen here carved stone into lace, into screen, into romantic visions.

Amazingly, descendants of the original owners occupy most of these old buildings and shops. They are proud, mustachioed Rajput men with flashing smiles, wearing brilliant turbans, gold earrings and pointed-toe slippers. The women too are bold and wonderful in their brightly colored Rajasthani gagharas and odhanis (gowns and half-veils) and bangles of ivory and silver.

The town was western Rajasthan’s great trade center on the caravan route between India and Central Asia. Founded in 1156 by Rawal Jaisal, a Rajput clan king, Jaisalmer grew wealthy from levies imposed on the passing caravans of camels carrying gold, silver, silks, indigo, ivory, sandalwood, muslin and opium. (Under both the Moguls and the British, opium was a lucrative and legal trade commodity.)

The town was western Rajasthan’s great trade center on the caravan route between India and Central Asia. Founded in 1156 by Rawal Jaisal, a Rajput clan king, Jaisalmer grew wealthy from levies imposed on the passing caravans of camels carrying gold, silver, silks, indigo, ivory, sandalwood, muslin and opium. (Under both the Moguls and the British, opium was a lucrative and legal trade commodity.)

The Rajputs, a warrior caste who settled in northwest India 1,000 years ago, are thought to be descendants of the Huns. Their chivalry, valor, sense of honor and clan loyalty is legendary. When Akbar, the invading Mogul emperor, finally defeated the Rajputs at Ranthambhor Fort in 1569, he was so impressed by their gallantry and martial skills that he invited them to be partners in power–an honor the Muslim ruler offered to no other Hindus. Rajput clan chieftains were even allowed to retain their land rights, being called Zamindar Rajahs in Mogul parlance.

In time, the Rajput royalty and rich imitated the sumptuous Mogul way of life, down to dress and manners. They built palaces and mansions in the Mogul style. Under the protection of the Mogul Empire, Jaisalmer enjoyed a period of peace and artistic splendor that lasted from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

It’s a 10-hour train ride from Jodhpur, the nearest city, to the end of the line at Jaisalmer. Even in second class ($6.50) the compartments are half empty (many people prefer the five-hour bus ride or take the flight from New Delhi) and we have both double seats to ourselves. We open the windows, stretch out and enjoy the desert scenes: scattered villages with circular huts, isolated hilltop fortresses, camels and turbaned riders, undulating dunes.

From the Jaisalmer station, it’s a five-minute auto-rickshaw ride to the outer gate of the fortress. We carry our bags up the cobbled passage that zigzags through the gateways of the successive citadel walls. Off the palace plaza, two immense wooden doors, tall enough for a camel and rider to pass through, open onto a courtyard green with flowering vines and banana trees.

The Paradise Hotel was originally the Diwanon ki Haveli, laid out like a small caravansary for merchants and businessmen invited into the fort by the maharawal, or prince. The smaller, ground level rooms scattered among several courtyards were for the camel pullers, loaders and stable boys. The merchants and dignitaries stayed in the rooms overlooking the ramparts.

The Paradise Hotel was originally the Diwanon ki Haveli, laid out like a small caravansary for merchants and businessmen invited into the fort by the maharawal, or prince. The smaller, ground level rooms scattered among several courtyards were for the camel pullers, loaders and stable boys. The merchants and dignitaries stayed in the rooms overlooking the ramparts.

We choose one of these upper rooms ($11 a night) with sandstone pillars, chiseled niches and a carved veranda that faces the desert sunrise. After rinsing off the travel dust, we stretch our legs with a short walk along the ramparts. We enter this winding walkway through a courtyard tiled with dung patties (gathered for cooking fuel) and guarded by two goats.

The smooth sandstone blocks of the ramparts are carved to fit each other without mortar and curved to follow the steep escarpment. Hundreds of sandstone cannon balls, made to be hurled down for defense, have been left scattered along the way. Passing beneath a stone veranda, we hear the clink of silver bracelets–a woman leans out, gazing over the desert, her unfastened veil an explosion of color against the cloudless sky. Camels walk around the base of the 250-foot hill; the melody of their tiny bells is the sound of the Thar Desert.

Slowly we succumb to the pervasive sense of fantasy. We return like sleepwalkers to the Paradise Hotel and climb to the rooftop veranda for the sunset. The young boy who delivers our tea sings as he climbs the stone steps. When the sun drops below the dunes, the warm January day turns suddenly cool.

In the morning we poke around the hilltop fort. It has the feel of a small island: pocketsize, easy to navigate. In the cobbled foot lanes among the stone houses and small havelis there are cows to squeeze by and children at play. Women wash clothes in hollowed-out cubes of sandstone, glazed to amber by centuries of use. Gentlemen with giant gray mustachios squat on doorsteps in front of white or blue-washed sandstone houses. Families gather on cushions for a meal inside cool cavernous rooms, many of which are painted lime or peach and glow with curtained sunlight.

In the morning we poke around the hilltop fort. It has the feel of a small island: pocketsize, easy to navigate. In the cobbled foot lanes among the stone houses and small havelis there are cows to squeeze by and children at play. Women wash clothes in hollowed-out cubes of sandstone, glazed to amber by centuries of use. Gentlemen with giant gray mustachios squat on doorsteps in front of white or blue-washed sandstone houses. Families gather on cushions for a meal inside cool cavernous rooms, many of which are painted lime or peach and glow with curtained sunlight.

Hindu and Jain (its offshoot) temples, 600 years old and filled with countless icons and images, are still in use. Of more recent vintage (1763-1820), the seven-story maharawal’s palace has dusty palanquins, the covered couches on which the royalty were transported by bearers, on view in rooms with domed ceilings, blue-tiled floors and colored glass windows. The palace is only the last in a succession of royal residences built on the same foundations.

Jaisalmer’s star fell with the fall of the Mogul Empire and the rise of the British in the 18th century. The British built railroads and opened the port of Bombay, eliminating the need for long-distance caravans. When ethics overcame economics earlier this century, the lucrative opium trade dwindled to a clandestine trickle. Finally partition and the closing of the border with Pakistan (about 50 miles west across the desert) turned out the lights. Havelis were boarded up. The population dwindled.

In 1975 Indira Gandhi, then India’s prime minister, made an unscheduled stop in Jaisalmer and ordered immediate measures taken to preserve this cultural and artistic desert gem. The maharawal then offered to loyal attendants and merchants parts of his fort for use as hotels, restaurants and shops. Revenue from the tourist sector has been slowly reviving the economy.

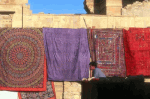

Many shops in the fort sell traditional handworked Rajasthani goods. In the Anand Embroidery House on the square called Dashera Chowk, Dalpat Singh has stacks of embroidered wall hangings (3 by 6 feet) piled everywhere. Simple hangings begin at $8, with the more intricate mirror work around $50. Singh will sew you a jacket out of any of his embroideries–labor about $5 extra.

Many shops in the fort sell traditional handworked Rajasthani goods. In the Anand Embroidery House on the square called Dashera Chowk, Dalpat Singh has stacks of embroidered wall hangings (3 by 6 feet) piled everywhere. Simple hangings begin at $8, with the more intricate mirror work around $50. Singh will sew you a jacket out of any of his embroideries–labor about $5 extra.

Around the corner, Rajmal Das sells brilliant Rajput turbans, tie-dyed into yellow, green, red and purple patterns. The 30-foot-long turbans, more than three feet wide, are compact bricks of crinkly cotton, and cost about $6 each. Rice grains, individually tied onto the cloth, resist the dye and form the traditional pattern of white dots running through the colors. These are popular with tourists who turn the cloth into exotic-looking summer outfits. As Rajmal Das demonstrates for us, when you stretch out one of these turbans, the threads break and the rice springs to the floor.

Other shops offer antique art and jewelry. We spend hours browsing through Rajasthani miniature paintings and pages out of old illuminated manuscripts displayed on shelves of sandstone. On our third morning, after enjoying the buttery sunrise from the reservoir, we breakfast at Midtown Restaurant near the outer gate of the fort (coffee, hearty omelet, a delicious apple crumble and deep-fried fritters called pakoras, which we took to eat later on). The bill is $3 for both of us.

Afterward, we explore the old royal town below the ramparts.

In Pansari Bazaar, a narrow little leather shop catches our eye. Bhawar Lal squats over his shoemaker’s last, pounding camel leather into those wonderful Rajput slippers ($6 a pair) we see everywhere. I sort through a stack, but can’t find a pair that fits me. Maria, my travel companion, on the other hand, easily finds a pair that suits her–plus a leather rucksack ($20), and two wonderfully tooled three-legged stools ($6.50 each). All are hand-stitched with leather threads. I find some slippers that nearly fit, but are really too small. Bhawar Lal sets to work oiling and pounding. Finally, craftsman and companion both persuade me they fit. (“They’ll stretch.”)

In Pansari Bazaar, a narrow little leather shop catches our eye. Bhawar Lal squats over his shoemaker’s last, pounding camel leather into those wonderful Rajput slippers ($6 a pair) we see everywhere. I sort through a stack, but can’t find a pair that fits me. Maria, my travel companion, on the other hand, easily finds a pair that suits her–plus a leather rucksack ($20), and two wonderfully tooled three-legged stools ($6.50 each). All are hand-stitched with leather threads. I find some slippers that nearly fit, but are really too small. Bhawar Lal sets to work oiling and pounding. Finally, craftsman and companion both persuade me they fit. (“They’ll stretch.”)

We amble over to the Royal Bazaar and in the small government emporium there we find the best selection and prices ($20) for beautiful hand-loomed and embroidered Jaisalmer blankets. Farther down we turn right and meander among sleepy, shadowy, residential lanes: more veils, dark eyes, turned-up toes, cows and camel carts.

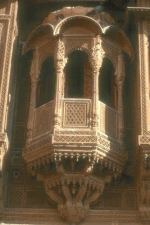

Suddenly we encounter a series of connected carved sandstone mansions that could only have been conceived in an opium dream and only created here. It is difficult to believe the galleries, porches and sun windows are really stone. Five brothers built these five Patva havelis between 1800 and 1860. Businessmen and opium exporters, they had concerns throughout India, Afghanistan and China.

As we admire the stonework, a man with a neatly curled mustache in a pinstripe shirt invites us to tour inside. Basant Jain tells us that the haveli belongs to his family and that he is in the antique business, just as his father was. Before that, “It was the opium trade.” Wall hangings, chandeliers and antique Rajasthani curiosities fill rooms with domed ceilings and arched entryways. Everything is for sale. We climb narrow stairs and spy on the lane below from an enclosed balcony whose windows are made of sandstone, planed and picked into near translucent screens.

Here is the place, if anywhere, to find a magic lantern with a genie inside. Jain hands me a 200-year-old carved opium box, challenging me to find its hidden compartment. Rubbing the polished wood, I cannot even detect the joints.

Here is the place, if anywhere, to find a magic lantern with a genie inside. Jain hands me a 200-year-old carved opium box, challenging me to find its hidden compartment. Rubbing the polished wood, I cannot even detect the joints.

My favorite haveli, however, is the Nathamalji ki Haveli. Two famous Jaisalmer stone-cutting brothers designed and carved this five-story building, completing it in 1885. One brother, Laloo, carved the left half and Hati, the right. Each chiseled his separate vision down to the accuracy of a single grain of sand. They met in the middle. The result, artistically asymmetric, is harmonious magic.

From the Nathamalji ki Haveli it is only a two-minute walk to the Amar Sagar Gate, the west gate of the walled town. Here the square (Gandhi Chowk) contains several rooftop restaurants and various tourist shops. The maharawal’s present home, the Mandir Palace, has been partly turned into a hotel (though the room we are shown is stuffy and smells of disinfectant) and sits off the square. An immaculately groomed camel, which in our minds at least i

s certainly the maharawal’s own camel, stands in the shady courtyard tethered to a tree. He looks imperious–not easy for a camel with its tail tied up.

Back at the Paradise Hotel, it’s another rooftop sunset and we are beginning to feel like members of the family. We ask Changra Shripat, the hotel’s owner/manager, to arrange a three-day camel safari out of Khuri (a desert village about 20 miles southwest of Jaisalmer, recommended as a starting point by a Rajasthani friend). Shripat makes a quick phone call and arranges everything.

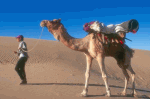

“Ourah! hep!! hep!” Gen Singh, my camel driver, calls out the next morning. The fuzzy little ears of the camel twist around and we break into a trot. We pass pristine Rajput villages of mud and wattle and oases marked with ancient sandstone cenotaphs, monuments honoring warrior ancestors. We make camp at the base of dunes whose sand runs like water when disturbed, peeling off in fluid avalanches that rise for 50 feet. The daytime world is sand and scalding sun. The nighttime is wild with shooting stars. Out of such a desert, who could have dreamed up the golden city of Jaisalmer?

“Ourah! hep!! hep!” Gen Singh, my camel driver, calls out the next morning. The fuzzy little ears of the camel twist around and we break into a trot. We pass pristine Rajput villages of mud and wattle and oases marked with ancient sandstone cenotaphs, monuments honoring warrior ancestors. We make camp at the base of dunes whose sand runs like water when disturbed, peeling off in fluid avalanches that rise for 50 feet. The daytime world is sand and scalding sun. The nighttime is wild with shooting stars. Out of such a desert, who could have dreamed up the golden city of Jaisalmer?

To contact Carl Duncan go to www.carlduncan.com or [email protected]

GUIDEBOOK

Getting there: By air: Air India and/or United (code share) fly direct from LAX to New Delhi with one stop in Hong Kong. United, Lufthansa and British Air fly from LAX to New Delhi through Europe with one change of plane. Singapore Airlines flies through Asia, with one change of plane in Singapore Air India offers direct flights from New Delhi to Jaisalmer on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. There are daily morning train departures from Jodhpur to Jaisalmer, 10 hours. The Rajasthan Tourist Development Corp. (RTDC) offers direct luxury bus service between Jodhpur and Jaisalmer. Five hours including a tea stop is $2.50.

Where to stay: There are about 60 hotels and guesthouses in Jaisalmer, 10 of which are inside the fort.

Hotel Paradise, on the fort, 19 rooms, seven on the ramparts with attached baths; rates $5-$20; telephone from Los Angeles 011-91-2992-52674.

Hotel Jaisal Castle, 186, on the fort, 11 rooms with attached baths; single $15, double $20; tel. 011-91-2992-52362.

Hotel Mandir Palace, Gandhi Chowk, old town, 11 rooms with attached baths; single $18, double $23; tel. 011-91-2992-52788.

RTDC Moomal Hotel; rates $6-$15; tel. 011-91-2992-52392. The RTDC bus to/from Jodhpur stops here.

For more information: Government of India Tourist Department, 3550 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 204, Los Angeles, 90010; tel. (213) 380-8855.