Nov 1999, Vol. 4 No. 2

In the rugged hills of the Whetstone Mountains, about 40 miles south of Tucson, Arizona, amateur cavers Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen found the “motherlode” More precious to them than gold was their 1974 discovery of an untouched natural treasure, a living cave with growing calcite formations, hidden under the desert floor for more than a million years.

In the rugged hills of the Whetstone Mountains, about 40 miles south of Tucson, Arizona, amateur cavers Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen found the “motherlode” More precious to them than gold was their 1974 discovery of an untouched natural treasure, a living cave with growing calcite formations, hidden under the desert floor for more than a million years.

Equally amazing are the steps Tufts and Tenen took to protect their remarkable find from vandalism and destruction. Rather than trumpeting the news of their discovery, the two men, then in their mid-20s, adopted a 14-year code of silence, going so far as making selected friends and loved ones sign documents of secrecy, so as to protect the caves.

Almost a quarter century later, Jay Ream, Chief of Operations for Arizona State Parks, would describe Tufts and Tenen as “two kids chasing the smell of bat guano.” (Although mountainous limestone terrain and the occasional sinkhole are the landmarks spelunkers look for when searching for caves, a whiff of odiferous bat guano is the telltale sign.)

The road to discovery was a long one. In 1966, Tufts and a few of his college buddies were feeling frustrated by their lack of success in finding an “undiscovered” caves. On one of their many weekend trips into the Whetstones, they bumped into a miner digging in the Lone Star Mine, in the Coronado National Forest just west of the private Kartchner ranch. They asked the miner if he knew of any caves in the area. He didn’t, but he did tell them about a nearby sinkhole where he had observed some high school kids exploring the terrain.

The sinkhole was on private land, owned by a rancher named James Kartchner. Kartchner, who would not learn about the cave that would later bear his name for more than 30 years, later recalled the hollow sound made by his horses’ hoofs when they rode over certain areas in the limestone hills while rounding up cattle.

After many hours of searching, Tufts found the sinkhole and, in it, an opening leading into a small chamber. The two cavers found no evidence of the existence of a larger cave and, concerned that the sinkhole might be unstable, they abandoned further exploration. While Tufts had no expectations of finding a cave, out of habit, he marked the site on his topographical map.

On an autumn day seven years later, Tufts, while caving in the same area, decided to further explore the sinkhole. While wandering near its perimeter, he discovered a second tunnel and hypothesized about the possibility of a passage between the two holes. When Tufts and Tenen returned the next weekend for further exploration, they found the small chamber as they remembered it.

Searching more carefully this time, the two men found a small opening in the rocks. From it, amid the cool air of the chamber, seeped a whiff of warm guano-scented air.

Tufts and Tenen knew they were on to something big. They wasted no time squeezing into the narrow opening—and discovered a second chamber, littered with footprints and broken stalactites that spoke of visits from the teenagers they had heard about.

The cavers continued their search of the chamber, finding a 10-inch high crawl space, which extended into a narrow twenty-foot tunnel. The tunnel ended abruptly at a wall, marred only by a small hole. As Tufts peered through the blowhole, a breeze extinguished his carbide light.

Adrenaline began to pump through Tufts’ body. The velocity of the guano-scented air meant that it had to be coming from a large underground chamber. Highly motivated, Tufts and Tenen began to chip away at the blowhole, with a sledgehammer.

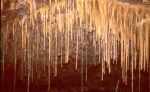

After enlarging the blowhole enough to squeeze through, Tufts and Tenen crawled through a 50-foot long guano-covered tunnel. Then suddenly, they emerged into a 300-foot long passage, one high enough for them to walk upright. The cavers stood stunned, surrounded by fragile glass-like soda straws, formations that grow into stalactites as the droplets of water seep through limestone and calcium carbonate. There were no footprints, or other evidence that a human being had ever entered this wondrous cave. Carefully, the young men retraced their steps—knowing that touching one of the numerous mineral formations could destroyed a structure that took a million years to create.

They emerged changed, weighted down by the awesome responsibility of protecting their discovery—a living cave dripping with an awesome variety of mineral and rock formations, undiscovered by humans since its formation. If the word got out, the cave could be vandalized or damaged by enthusiastic amateurs. They decided to keep it a secret until they could decide what to do.

It took a year for Tufts and Tenen to fully explore the two-and-a-half mile cave, which was made up of two main chambers—each 100 feet high and the size of a football field—and 26 smaller attached rooms. Whenever they drove to the Whetstones, the cavers hid their cars while they were exploring, so as not to give away the location of the cave entrance. As they explored, they marked their trail only with Popsicle sticks. They removed their shoes, wearing only socks so as not to leave footprints. If they accidentally broke a formation, they glued it back with dental cement. They named the cave Xanadu.

The weight of the responsibility of their discovery continued to grow. The pristine cave was too accessible, only nine miles from a major highway. Tufts and Tenen decided that the only way to protect the cave was to develop it as a commercial attraction, or get federal or state protection. By this time, using aliases, they had visited other tourist caves, making comparisons of their discovery and learning about the cost of commercial development.

The weight of the responsibility of their discovery continued to grow. The pristine cave was too accessible, only nine miles from a major highway. Tufts and Tenen decided that the only way to protect the cave was to develop it as a commercial attraction, or get federal or state protection. By this time, using aliases, they had visited other tourist caves, making comparisons of their discovery and learning about the cost of commercial development.

In 1978, they went to visit the landowners. By then, Tufts and Tenen had been trespassing on the Kartchner ranch for four years. The family was at first annoyed, but then they heard about the cave. Sworn to secrecy, the Kartchner family worked with the cavers. Despite all the secrecy, however, the caving world is a small one and rumors inevitably spread. When curious spelunkers trespassed on the ranch, the pistol-packing Kartchner brothers rode up on horseback to escort them off the property.

The Kartchners, who owned the ranch since 1941, couldn’t have anticipated that the development and commercialization of the cave would cost more than $28 million. They brought in then-Governor Bruce Babbitt, who viewed the cave and, under a veil of secrecy, helped to guide the property into public ownership.

Babbitt led the cavers and ranchers through the legislative process of designating the cave as a state park. In 1988, when the state of Arizona bought the land, only six members of the legislature knew that the dummy legislation actually authorized the creation of the James and Lois Kartchner Caverns State Park. Tufts and Tenen had seen their dream come to fruition.

Touring Kartchner Caverns

On a cool day almost 25 years ago, Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen found the cave every spelunker dreams of discovering. The responsibility these young men took to preserve the pristine space will be appreciated by the visitors who tour Kartchner Caverns, slated to open in November, 1999.

On a cool day almost 25 years ago, Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen found the cave every spelunker dreams of discovering. The responsibility these young men took to preserve the pristine space will be appreciated by the visitors who tour Kartchner Caverns, slated to open in November, 1999.

The grand opening is expected to draw worldwide attention. Kartchner is a “wet” living desert cave, and caving experts rank it as one of the finest for the richness and variety of its mineral deposits. It is anticipated that Kartchner will be the second largest tourist attraction in the state of Arizona, after the Grand Canyon.

The fourteen years spent exploring the cave and outfitting it for public access have been tedious and costly. Cost estimates run to $27,000 per square foot, with a total investment of $28 million. The expense comes from efforts to protect the wetness of the cave and ensure continued growth of formations, while still allowing visitor access.

To protect the fragile ecosystem, visitors will walk through a descending 40-foot-long shaft, passing through an air curtain before entering an air-locked conservation chamber designed to remove any spores collected on clothing. Protective shields, unnoticeable to the visitor, line the trail to collect any foreign material carried on shoes.

The park service will convey an emphatic message of caution. The trail winds through the mineral formation, stalactites, and stalagmites. One curious touch of a hand could destroy a formation a million years in the making. Lighting the interior of the cave is an ongoing challenge for the experts. They will continue to work with the lighting until they feel they have achieved the amount of wattage that will not create drying heat . At the same time they need enough light to prevent a visitor from stumbling.

A tour through the two main chambers, the Big Room and the Throne Room, is enthralling. Stalactites and stalagmites, which grow only one-tenth of a millimeter in a year, appear in all shapes and forms. Droplets of water seep through the limestone, creating the soda straws that will eventually become stalactites. When water hits the floor, carbon dioxide escapes, leaving an irregular layer of calcium carbonate that grows into stalagmites. The walls of Kartchner are covered with helictites, formed by water forcing its way through tiny fissures. Formations that look like frozen waterfalls, called draperies or curtains, have been formed by water deposits dripping on the underside of a sloping ceiling. A variety of iron deposits have created colorful formations called “cave bacon”; other deposits look like fried eggs in spite of their smooth, hard surfaces.

A tour through the two main chambers, the Big Room and the Throne Room, is enthralling. Stalactites and stalagmites, which grow only one-tenth of a millimeter in a year, appear in all shapes and forms. Droplets of water seep through the limestone, creating the soda straws that will eventually become stalactites. When water hits the floor, carbon dioxide escapes, leaving an irregular layer of calcium carbonate that grows into stalagmites. The walls of Kartchner are covered with helictites, formed by water forcing its way through tiny fissures. Formations that look like frozen waterfalls, called draperies or curtains, have been formed by water deposits dripping on the underside of a sloping ceiling. A variety of iron deposits have created colorful formations called “cave bacon”; other deposits look like fried eggs in spite of their smooth, hard surfaces.

The single trail used by the cavers during their exploration remains at the muddy bottom of the Throne Room. This mud, which experts think might be as much as 12 feet deep, provides the moisture crucial to maintaining the caves’ humidity. During rainy years, water seeps through the limestone covering the mud to create a river.

In the summer months, several thousand bats use the Big Room as a maternity ward. While the bats are birthing in the cave, there are no tours scheduled to disturb them. They are left in darkened privacy. Cave experts see the well-being of the bats as a barometer of the public’s impact on the cave. Bats do not currently nest in the Throne Room, although there is evidence of bat guano dating back 35,000 years.

As the summer heat climbs into the hundreds, the interior of the cave maintains a temperature of 68°F and a humidity of 99%. With the precautions taken, any loss of moisture caused by touching, lighting, or foreign materials can’t stop the magnificent formations from growing.

One of the unique features of Kartchner Caverns is it accessibility to the public. The cave is located only nine miles from I-10, Arizona’s major southern interstate.

Directions: To reach Kartchner Caverns from Phoenix or Tucson, take I-10 east to the Highway 90 ( Sierra Vista/Ft. Huachuca ) exit. The cave is located nine miles south of the exit. Approximate driving time is two hours from Phoenix; 45 minutes from Tucson.

For tour reservations: call 520-586-CAVE, or go to www.pr.state.az.us